The modern sandbox game, pioneered primarily by Rockstar and the Grand Theft Auto series and further popularized by Ubisoft’s modern open-world formula found in Assassin’s Creed, has become one of the most common AAA genres in the industry. No matter what type of sandbox game you’re playing, be it the GTA brand of city driving, Skyrim/The Witcher 3’s awe-inducing scale, or The Division’s massive recreation of Manhattan, they all have one obsession in common: make the world as huge as possible, because that theoretically makes for a better game.

But why is that? Why do some games with not nearly enough interesting content or mechanics don such a large world when the largest thing it contributes is time-spent-in-car/holding the sprint button/clicking fast travel? Why does it seem as though developers chase the goal of creating a massive space when it is sometimes to the game’s complete detriment?

The answer is simple, but nonetheless misguided. Large sandboxes are impressive to see, especially when they look as good as they do in games like Mafia 3 and The Division. Couple that sentiment with the immersion of convincing worlds, and it amounts to a general thought process that leads to “bigger world equals better game.” But so often, that’s just not true. Even some of the greatest games in their genre, Watch Dogs 2 and The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim, suffer from their wide-open landscapes being underutilized.

Both games, for how great their gameplay or side quests might be, are just too big for their own good. Skyrim’s main quest takes you on a brief tour of every main city and the villages between, but so much of the game’s world is Generic Cave #47 and yet another Draugr ruin. A lot of the space is filler, and that’s fine, but it would be a better game (that is still plenty long, mind you) without content that drops the qualitative curve.

The same can be said of Watch Dogs 2’s beautiful recreation of the Bay Area. Filler content like micro-stealth encounters and inoffensive-but-dreadfully boring side activities litter every corner, but the game would be better off without it all. That doesn’t even account for so much landscape that has no use, especially the gigantic body of water separating the game’s three main cities by bridge. Ah yes, the Golden Gate and Bay Bridge, two very beautiful and very pointless things to drive across over and over again in the context of a video game.

As a result of this, fast travel has become a lazy solution to a problem of travel fatigue. What’s the point of running or driving down the same well-rendered roads for the 12th time when they have no real gameplay relevance? Just zip over to the action!

But sandbox games should do better than fast travel. They should have better-designed worlds that don’t need fast travel, either because the journey itself can be fun the 20th time around, or the open-world is concise enough to be a non-issue.

Both titles should strive for more interaction with the player between active missions. Watch Dogs 2, in its truest sense, is a stealth game with a dash of puzzle-solving and platforming in the form of drone navigation. The driving is fine, but its also pointless. It’s just a means to get to the actual fun of the game when you choose to not fast travel. A smaller environment would not only highlight the under-utilized and fun-as-hell parkour mechanic, but also trim the unnecessary fat from one beast of a game.

A smaller world for Skyrim would simply alleviate or delegitimize its worst aspects: the more mind-numbing buffer quests, over-reliance on fast travel, and slow movement speed (even on horseback). The meat of Skyrim is instead found from the rich characters of its large cities, the dynamic nature of its world, and the hand-crafted side content that often outshines the Dragonborn’s main story.

This of course, would also leave more time for developers and designers to spend more time on the locations that the games actually focus on. The block around the DeadSec HQ or Skyrim’s main hubs could be feature more fully-realized building interiors, people to talk to, and things to customize. More importantly, designing a game around a more limited scope and raising the bar of what content is worth having raises the scale by which a game is judged–if a game is made up of only its greatest strengths, those strengths are what the game IS.

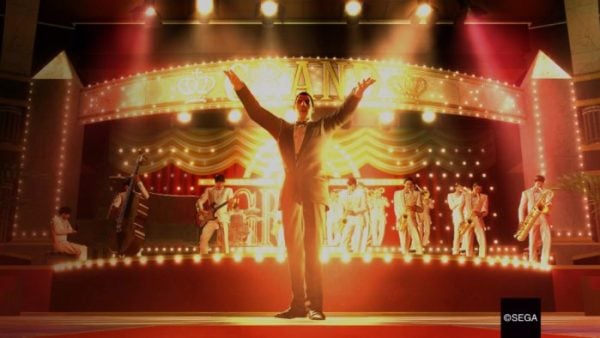

And this is something that a game like Yakuza 0 understands oh so well.

Yakuza has everything you want in an open-world game: a great story, good characters, a vibrant world, interesting side content, circa-1988 SEGA arcades, breakdance fighting, you know, the works. It also has a total world size of about five square blocks at any given time. That sounds small, but in practice, it couldn’t feel more perfect. This is because Yakuza 0’s world is scaled based on the amount of quality content the game has to offer, not the other way around.

There is no room for filler: just compelling stories, some of the best humor seen in games (especially one localized from Japanese), and a combat system so ridiculous and easy that it’s impossible to not have a good time. Sure, the game benefits from taking place in a densely-packed city like Tokyo, but it still shows plenty of intelligent restraint.

The game could be about driving around a massive recreation of Tokyo, but instead it’s about strolling around lovingly crafted recreations of smaller boroughs in a much larger city. It’s a game about local issues: strong-arming Yakuzas, real estate beefs, nightclub wars, and sometimes even taxes.

Treks from destination to destination that would usually be one click of fast travel or seven minutes of driving in other games amounts to a quick jog down the street in Yakuza, maybe beating up some thugs or increasing your friendship with townspeople on your way. You spend your time traveling to objectives actually playing the game, instead of using handy shortcuts left by developers to make sure you don’t have to play the part they know is boring.

Yakuza accomplishes the feat of making its sandbox consistently un-boring, and that should be celebrated. Nothing feels missing because of its smaller size. Rather, it feels like a more complete game start to finish.

This is not to say that the perfect sandbox formula is one of a small world packed with the best content, but it is part of a better solution to a common problem in the genre. There is a lot to love and appreciate about a beautifully rendered city or fantasy world that boasts an impressive scale, but for that to be fully justified, the world should be packed with purposeful content that uses its space better, not generic dungeons or poorly-made side activities.

But in lieu of that, it’s worth considering a scaled-down world that creates a tighter and more consistent stream of quality gameplay.